13. Linking

Lec 13: Linking¶

Static Linking¶

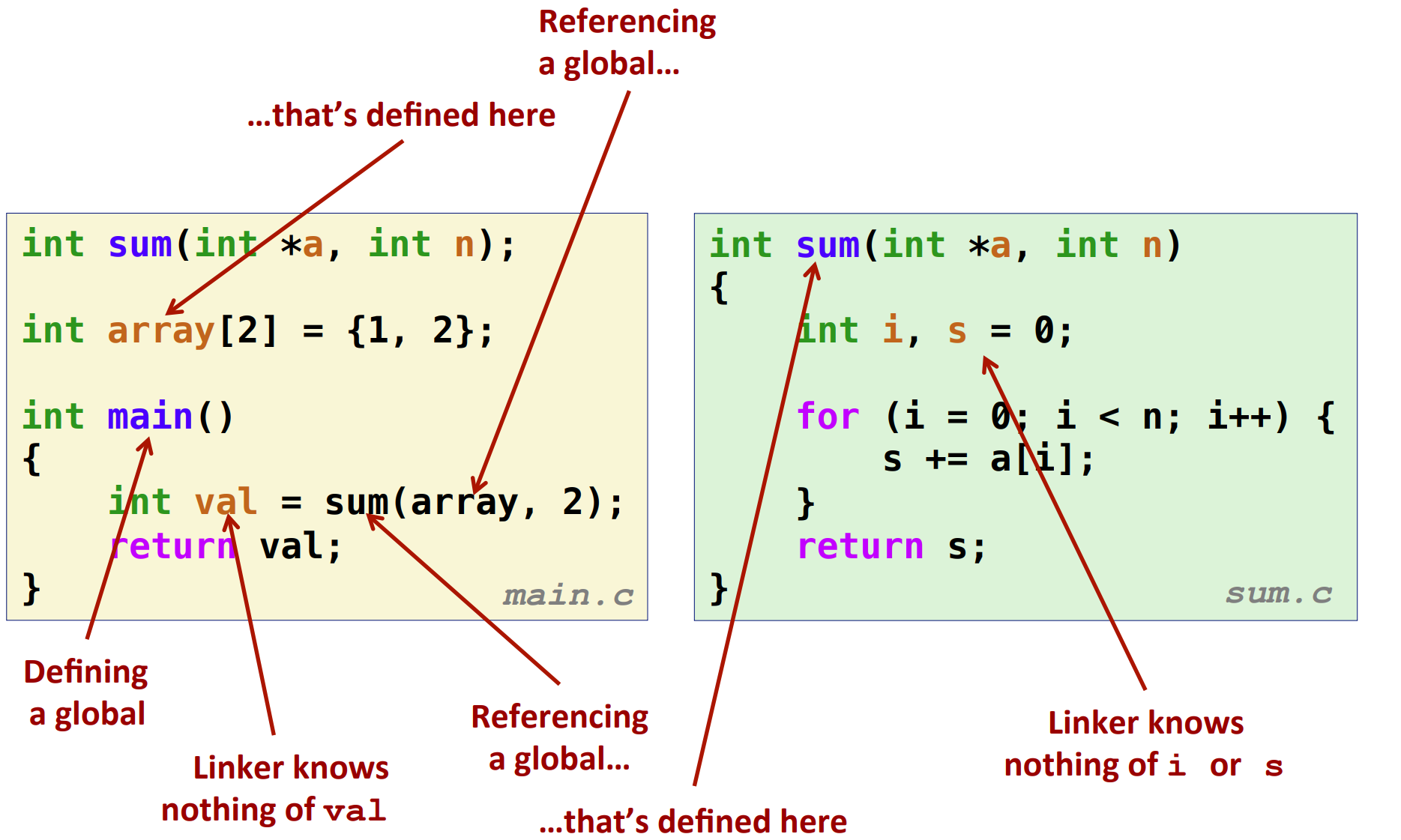

Suppose we have two .c files:

/*

* main.c

*/

int sum(int *a, int n);

int array[2] = {1, 2};

int main()

{

int val = sum(array, 2);

return val;

}

/*

* sum.c

*/

int sum(int *a int n)

{

int i, s = 0;

for (i = 0; i < n; i++) {

s += a[i];

}

return s;

}

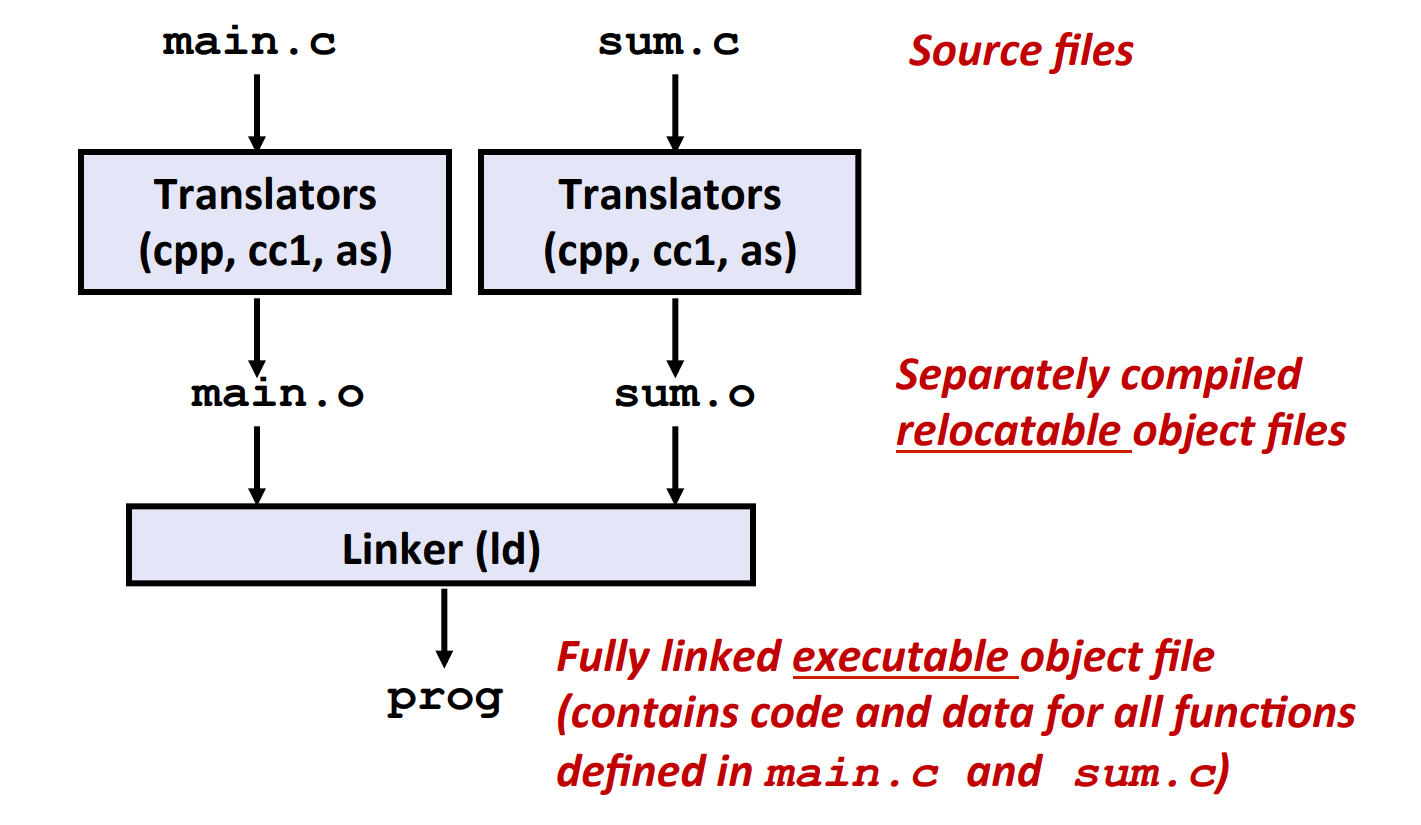

The overall procedure is shown below:

- C preprocessor:

cpp - C compiler:

cc1 - Assembler:

as - Linker:

ld

Why Use Linkers?¶

Why not just put all codes into one file?

Reason 1: Modularity

- Program can be written as a collection of smaller source files, rather than one monolithic mass.

- Can build libraries of common functions (more on this later)

- e.g. Math library, standard C library

Reason 2: Efficiency

- Time: Separate compilation

- Change one source file, compile, and then relink.

- No need to recompile other source files.

- Space: Libraries

- Common functions can be aggregated into a single file...

- Yet executable files and running memory images contain only code for the functions they actually use.

What Do Linkers Do?¶

Three Kinds of Object Files¶

- Relocatable Object File (

.ofile)- Contains code and data in a form that can be combined with other relocatable object files to form executable object file.

- Each

.ofile is produced from exactly one source (.c) file

- Each

- Contains code and data in a form that can be combined with other relocatable object files to form executable object file.

- Executable Object File (

.outfile)- Contains code and data in a form that can be copied directly into memory and then executed.

- Shared object file (

.sofile)- Special type of relocatable object file that can be loaded into memory and linked dynamically, at either load time or runtime.

- Called Dynamic Link Libraries (DLLs) by Windows

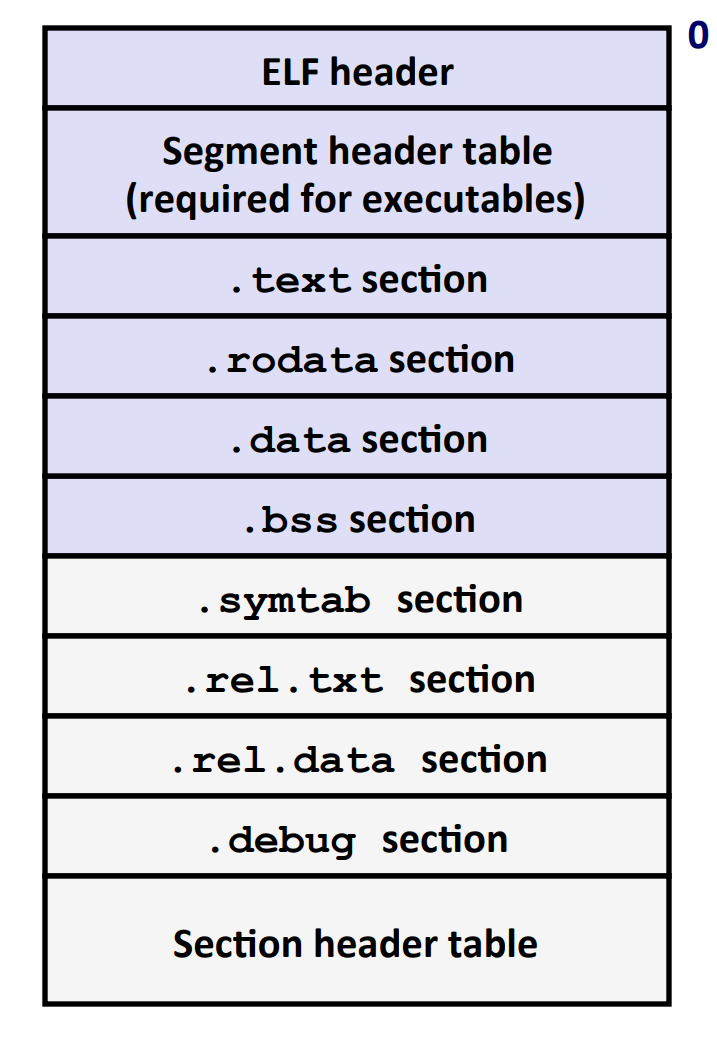

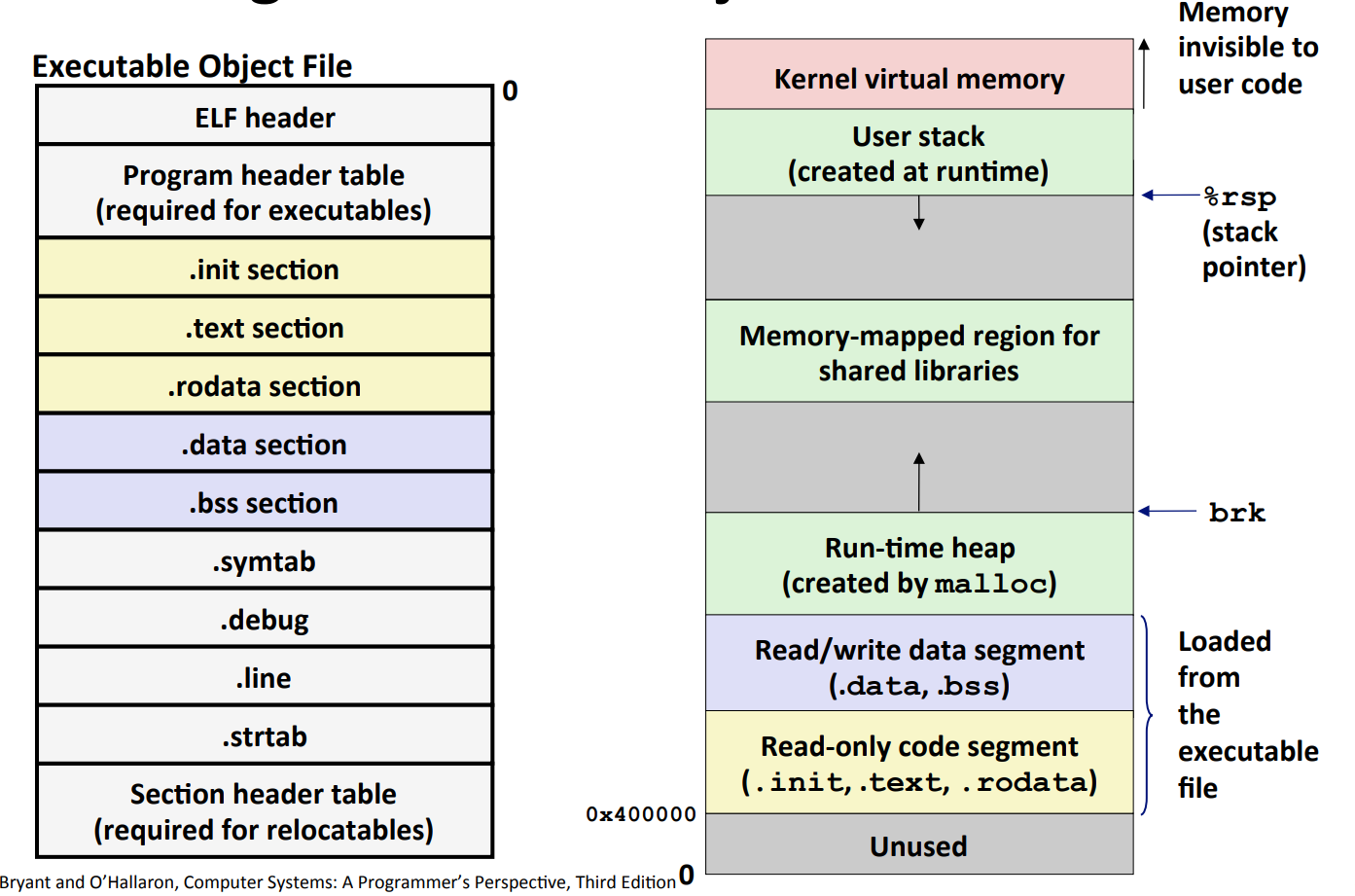

Object File Format¶

The standard format for object file is "Executable and Linkable Format (ELF)".

- General name is ELF binaries

ELF Object File Format¶

- Elf header:

- Word size, byte ordering, file type (.o, exec, .so), machine type, etc.

- Segment header table:

- Page size, virtual addresses, memory segments (sections), segment sizes.

.textsection (code indicator):- Code

.rodatasection:- Read-only data: jump tables, ...

.datasection:- Initialized global variables

.bsssection:- Uninitialized global variables

- "Block Started by Symbol"

- "Beginner Save Space"

- Has section header but occupies no space

.symtabsection:- Symbol table

- Procedure and static variable *names*

- Section names and locations

.rel.textsection:- Relocation info for

.textsection- i.e. Assembler, "I don't know where these symbols are located in memory, so linker, please fix these for me."

- Addresses of instructions that will need to be modified in the executable

- Instructions for modifying

- Relocation info for

.rel.datasection:- Relocation info for

.datasection- similar to

.rel.text

- similar to

- Addresses of pointer data that will need to be modified in the merged executable

- Relocation info for

.debugsection:- Info for symbolic debugging (gcc -g)

- Section header table:

- Offsets and sizes of each section

Linking And Executing Procedure¶

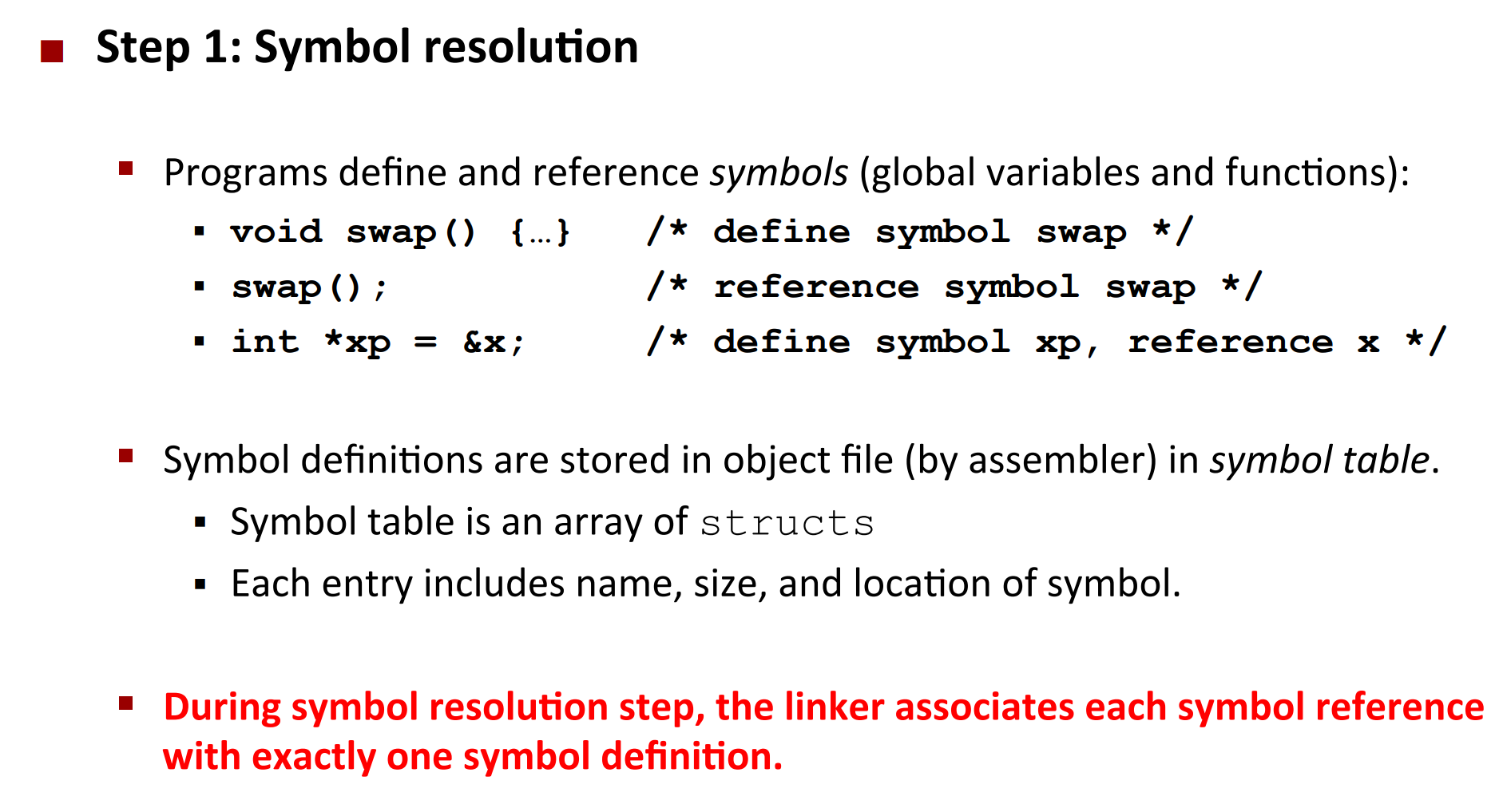

There are 3 kinds of linker symbols in total:

- Global symbols

- Symbols defined by module m that can be referenced by other modules

- e.g. non-

staticC functions and non-staticglobal variables

- External symbols

- Global symbols that are referenced by module m but defined by some other module

- Local symbols

- Symbols that are defined and referenced exclusively by module m

- E.g.:C functions and global variables defined with the

staticattribute - Local linker symbols are not local program variables

- it's a way to define "private functions" and "private variables" in C

Step 1: Symbol Resolutions¶

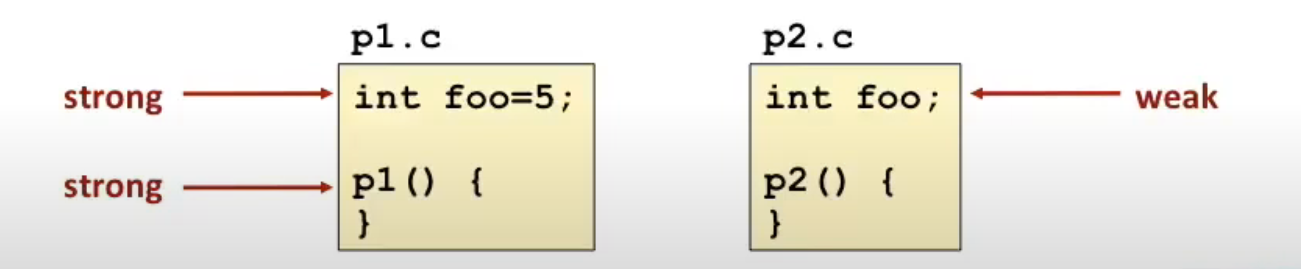

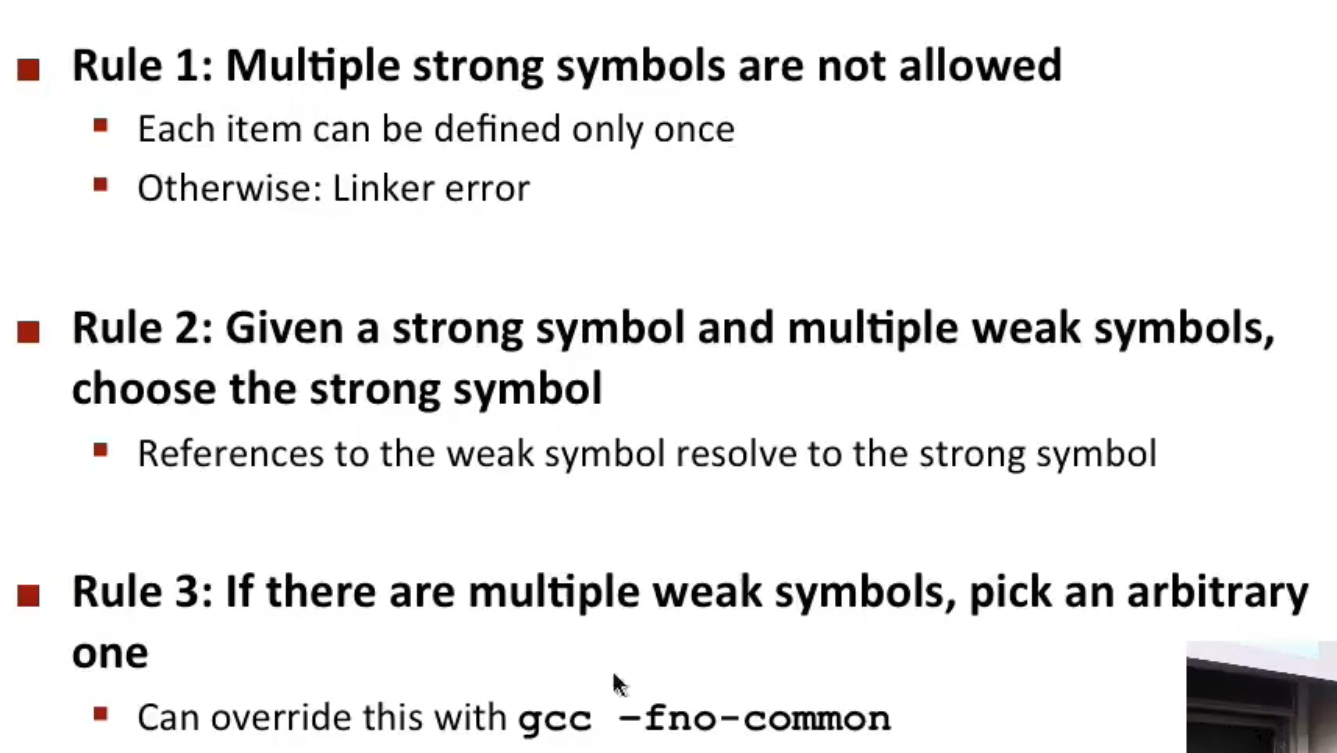

How Linkers Resolve Duplicative Symbols?¶

- Program symbols are either strong or weak

- Strong: procedures and initialized globals

- Weak: uninitialized globals

Linker's Symbol Rules¶

Bad Code¶

// main.c

int x = 0xa;

int y = 0x14;

##include <stdio.h>

void change();

int main() {

change();

printf("%x %x\n", x, y);

}

Then, the x in bad.c will overwrite x and y, resulting in

where 0x400921fb4d12d84a is the double precision representation of 3.1415926.

Rule of thumb:

- Avoid using global variables

- Otherwise

- use

static - Initialize if you define a global variable

- i.e. make it strong

- Use

externif you reference an external global variable

- use

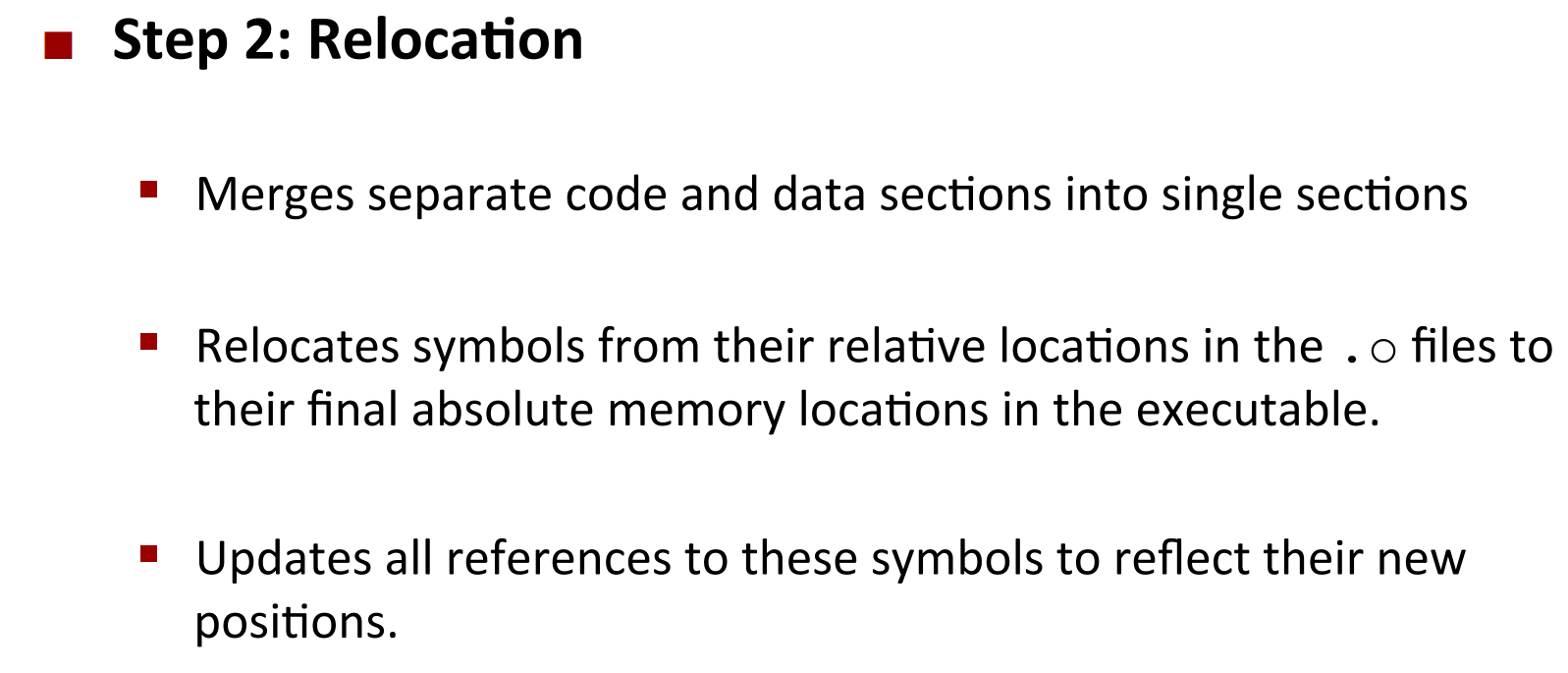

Step 2: Relocation¶

Relocation Entries¶

For this piece of code:

The assembly is (via objdump -r -d main.o):

0000000000000000 <main>:

0: f3 0f 1e fa endbr64

4: 55 push %rbp

5: 48 89 e5 mov %rsp,%rbp

8: 48 83 ec 10 sub $0x10,%rsp

c: be 02 00 00 00 mov $0x2,%esi

11: 48 8d 3d 00 00 00 00 lea 0x0(%rip),%rdi # 18 <main+0x18>

14: R_X86_64_PC32 array-0x4

18: e8 00 00 00 00 callq 1d <main+0x1d>

19: R_X86_64_PLT32 sum-0x4

1d: 89 45 fc mov %eax,-0x4(%rbp)

20: 8b 45 fc mov -0x4(%rbp),%eax

23: c9 leaveq

24: c3 retq

As you can see, 14: R_X86_64_PC32 array-0x4 means

- calculate the relative offset of array and *0x14

-

decrease it by 0x4, since the PC is at 0x18

- i.e.

(array - 0x14) - 0x4 = array - 0x18

- i.e.

-

fill this 32-byte offset at 0x14

Since array will be relocated during linking, we don't know exactly where it will be, so this patch is necessary.

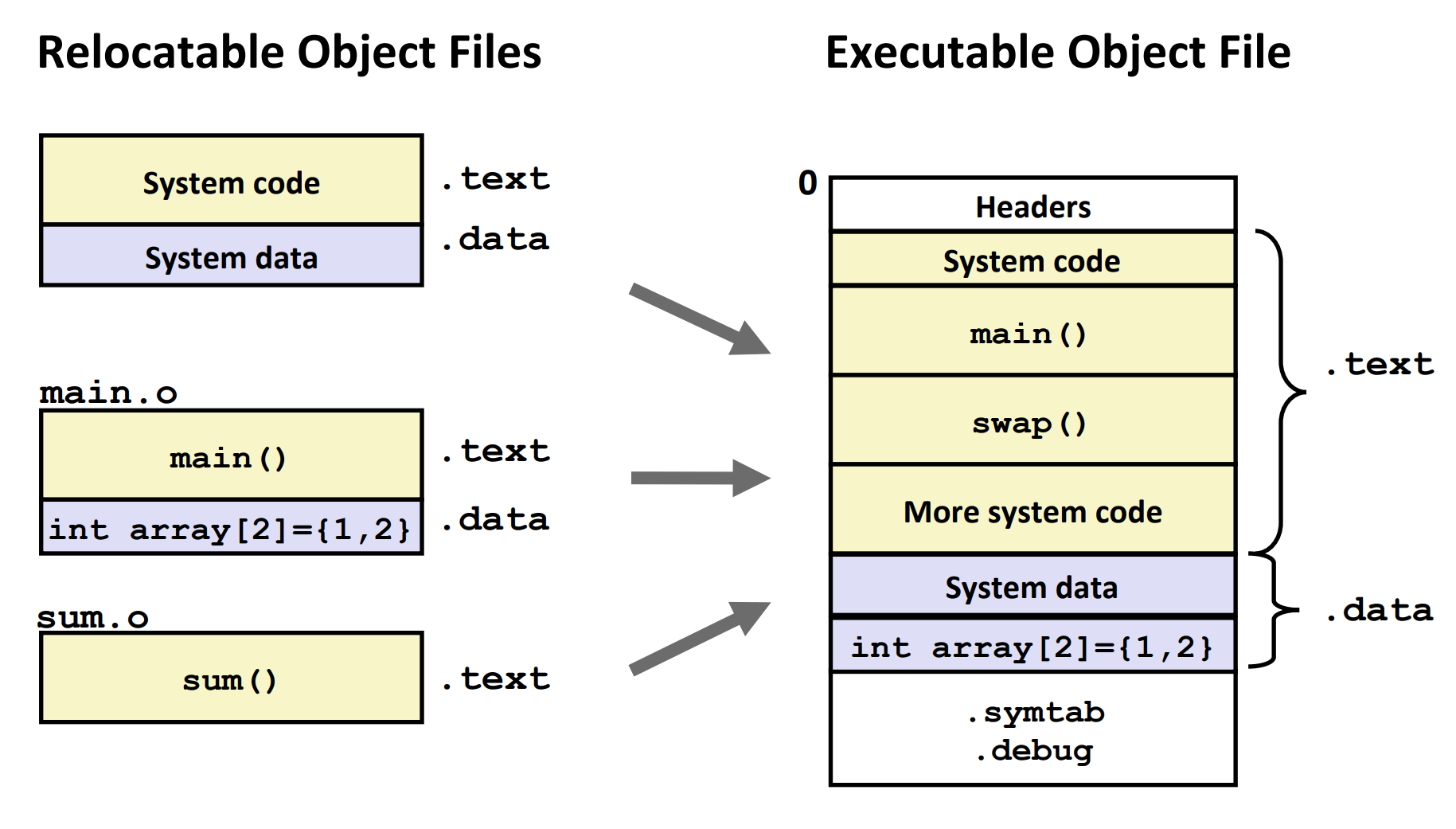

Step 3: Load Into Memory¶

-

The color indicates the correspondence of the segments of

.outfile and the memory regions where they are loaded. -

Note: There is a place called memory-mapped region for shared libraries between the huge gap of user stack and run-time heap.

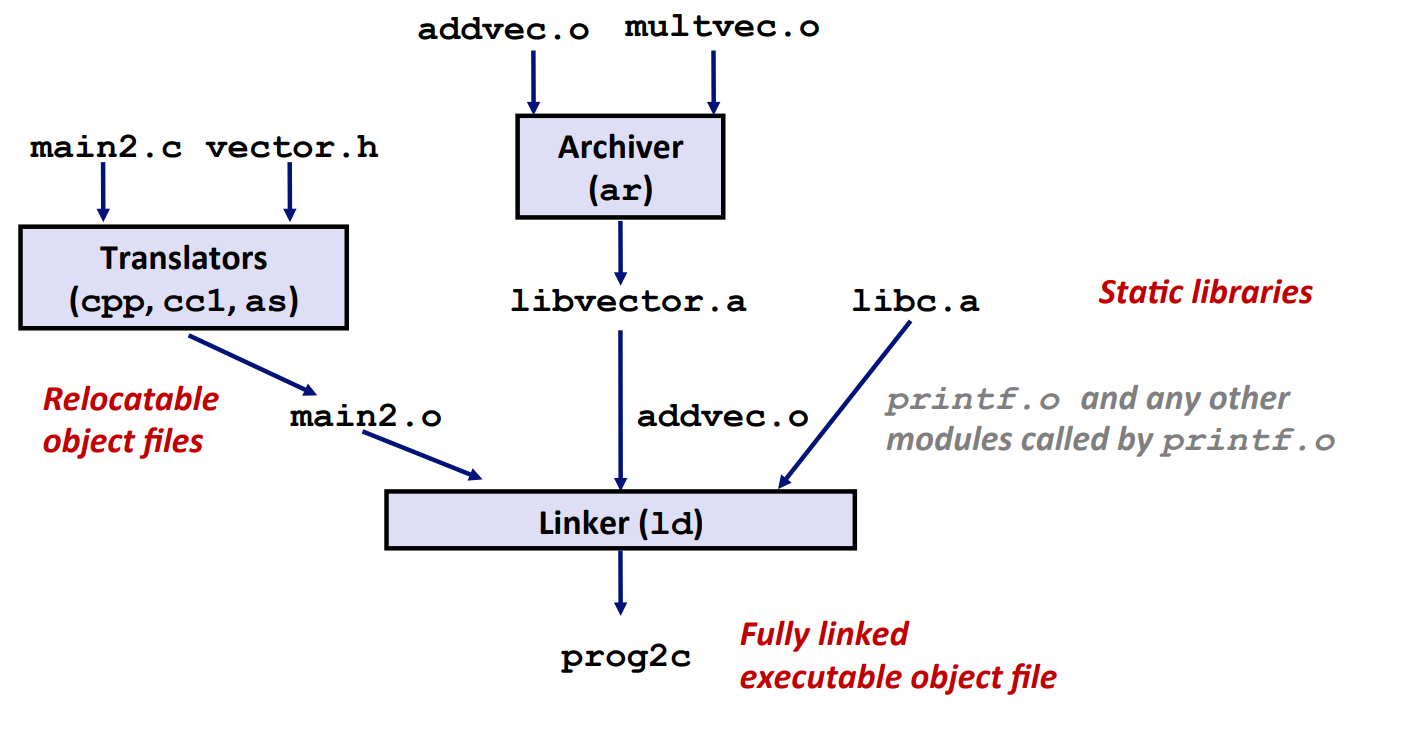

Packaging Useful APIs¶

How to package functions commonly used by programmers?

- e.g. math, I/O, memory management, string manipulation, etc

Given the linker framework so far, it can be awkward:

- Options 1: Put all functions into a single source file

- Programmers link big object file into their memory

- It's time and space inefficient

- Option 2: Put each function in a separate source file

- Programmers explicitly link appropriate binaries into their programs

- More efficient,but burdensome on the programmer

- i.e. ridiculous large command line to

gcc

- i.e. ridiculous large command line to

Old-Fashioned Way: Static Library¶

gcc has a default path to static libraries: /usr/lib/...

Linker's algorithm for resolving external references:

- Scan

.ofiles and.afiles in the command line order. - During the scan, keep a list of the current unresolved references.

- As each new

.oor.afile,obj, is encountered, try to resolve each unresolved reference in the list against the symbols defined inobj. - If there are any entries in the unresolved list at the end of the scan, then error.

Problem¶

Suppose you have a piece of C code:

##include <stdio.h> /* printf */

##include <math.h> /* cos */

##define PI 3.14159265

int main ()

{

double param, result;

param = 60.0;

result = cos ( param * PI / 180.0 );

printf ("The cosine of %f degrees is %f.\n", param, result );

return 0;

}

Then,

is okay,

whereas

is not okay, because main.c (later main.o) is scanned after libm.a and libc.a.

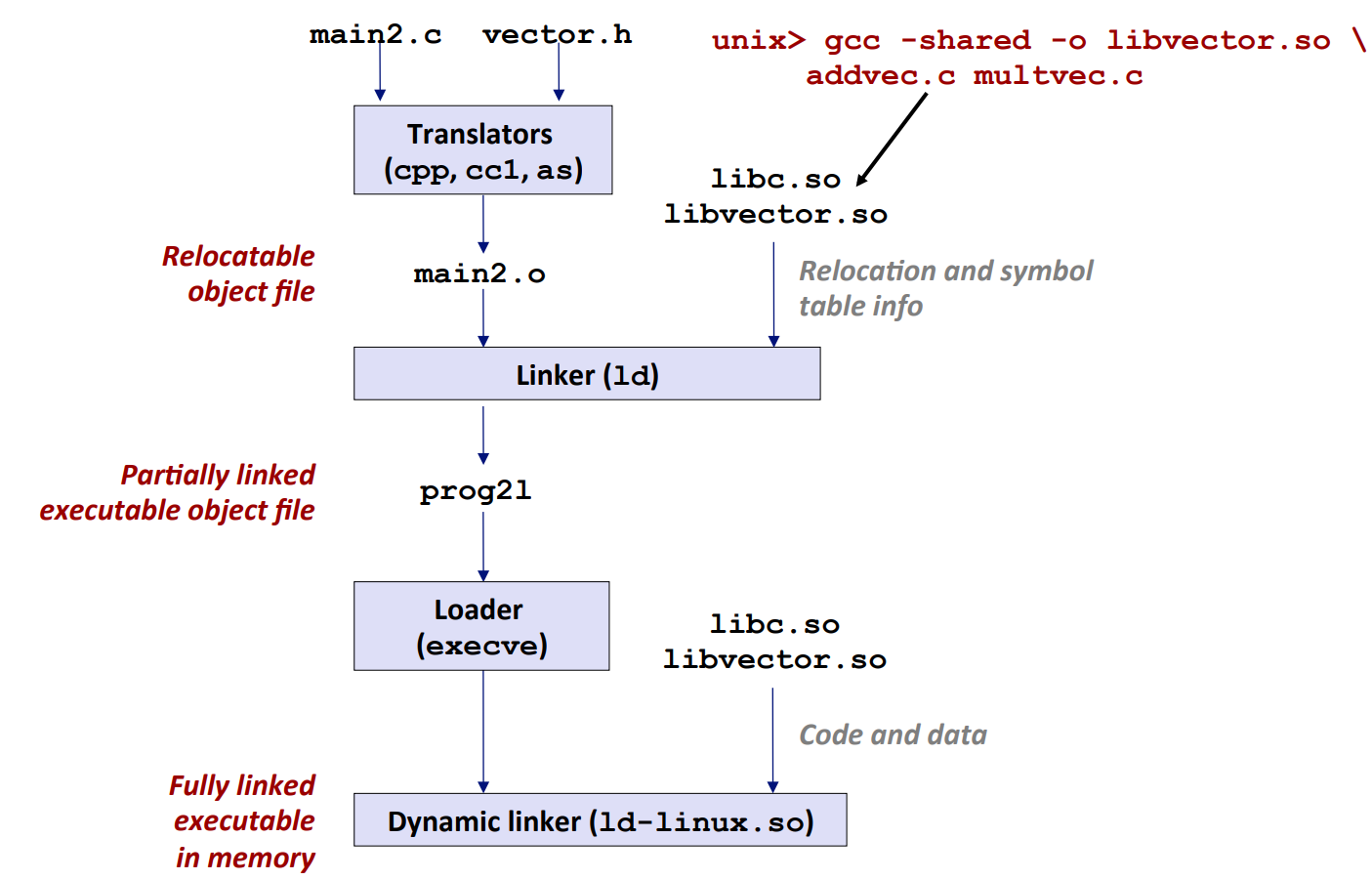

Modern Approach: Dynamic Linking¶

Unlike statically linked exes, the function calls in dynamically linked exes get linked not at linking time, but at load time.

And it can even get linked at runtime.

Runtime Dynamic Linking¶

/* main.c */

##include <stdio.h>

##include <stdlib.h>

##include <dlfcn.h>

long x[2] = {1, 2};

long y[2] = {3, 4};

long z[2];

void (* addvec) (long *v1, long *v2, long *vdest, unsigned int size);

int main()

{

void *handle;

char *error;

handle = dlopen("./libvector.so", RTLD_LAZY);

if (handle == NULL)

{

fprintf(stderr, "%s\n", dlerror());

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

addvec = dlsym(handle, "addvec");

if ((error = dlerror()) != NULL)

{

fprintf(stderr, "%s\n", error);

exit(1);

}

addvec(x, y, z, 2);

printf("z = [%ld %ld]\n", z[0], z[1]);

/* Unload the shared library */

if (dlclose(handle) < 0)

{

fprintf(stderr, "%s\n", dlerror());

exit(1);

}

return 0;

}

/* addvec.c */

void addvec(long *v1, long *v2, long *vdest, unsigned int size) {

for (int i = 0; i != size; ++i) {

vdest[i] = v1[i] + v2[i];

}

}

Then, use gcc -shared -fpic -o libvector.so addvec.c to generate shared object file.

And use gcc -o main main.c libvector.so -ldl to generate exe obj file.

-ldlstands forlibdl.so, which is used to linkdlfcn.h

Library Interpositioning¶

See here for details.

There are three interpositioning techniques in all:

-

on compilation

- 思路:使用本地的

malloc.h,在预处理阶段,替换main.c的头文件,从而达到预处理期替换函数的作用 - 使用

-I.flag - 注意:

mymalloc.c不能加-I.flag,从而mymalloc里的malloc/free不会被预处理成mymalloc/myfree - 流程:

- 先使用

gcc -E -I. int.c -o int.i将int.c通过我们自己的malloc.h进行预处理- 将函数替换成我们自己的函数

- 然后使用

gcc int.i mymalloc.c -DCOMPILETIME -o intc一条龙即可

- 先使用

- 思路:使用本地的

-

on linking

- 思路:使用 linker 的独特机制,i.e.

--warp, func,在 linking 时,将对func的引用解析成__warp_func,对__real_func的引用解析成func。从而达到链接期强制替换(引用)符号的作用。 - 流程:

- 先使用

gcc -DLINKTIME -c mymalloc.c和gcc -c int.c将两个源文件翻译成 obj 文件 - 然后使用

gcc int.o mymalloc.o -o intl -Wl,--wrap,malloc -Wl,--wrap,free,将所有 obj 文件里的- 符号

malloc当作符号__warp__malloc - 符号

__real__malloc当作符号malloc - 符号

free当作符号__warp__free - 符号

__real__free当作符号free

- 符号

- 先使用

- 思路:使用 linker 的独特机制,i.e.

-

at runtime

- 思路:使用 loader 的特殊机制,

- i.e. 如果 LD_PRELOAD 环境变量被设置为一个共享库路径名的列表,那么当你加载和执行一个程序,需要解析未定义的引用时,动态链接器会先搜索 LD_PRELOAD 库,然后才搜索任何其他的库。

- 从而,可以从外部指定一个函数将如何执行。也就是达到运行时替换动态链接库,从而替换函数地址的作用。

-

注意:原运行时打桩的代码是错误的,因为

printf也会用到malloc和free,从而导致无限循环。我们需要使用static变量来记录递归次数。我们只在malloc递归深度为 1 的时候进行输出。void *malloc(size_t size) { static int calltimes = 0; calltimes++; // ... if (calltimes == 1) printf(...) calltimes--; return 0; }free同理。 -

流程:这里不赘述。不过说到底,并不是 runtime interpolation,而是 load time interpolation。

- 思路:使用 loader 的特殊机制,